Worst Air Disaster

of All Time

On

March 27, 1977, a terrorist bombing, heavy fog, a slight problem with the

communications system at a critical moment, and an impatient senior pilot

combined to create what remains today the single most deadly accident in

aviation history.

What

is remarkable about this accident, aside from the record number of fatalities,

is that neither plane had been scheduled to be at Tenerife's Los Rodeos airport

that day.

Canary

Islands have long been a destination for European tourists with its resorts

rivaling the best of the Mediterranean. By 70s the islands had also become a

destination for Americans wishing to begin Mediterranean cruises. On the morning

of March 27th 1977, two planes full of such tourists departed for Los Palmas

Airport - one of two major airports in the Canary Islands.

The

first plane was a KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 747 operating as flight KL4805 on

behalf of the Holland International Travel Group. Piloting the plane was KLM's

chief 747 training captain Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zantent, who also had been

featured in KLM advertising - including the in-flight magazine aboard flight

KL4805. He had been with KLM since 1947 and had trained almost all other KLM 747

pilots and co-pilots. This charter flight was a rare one for van Zantent as he

had been spending much more time training other pilots than flying.

Captain

van Zantent departed Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport that morning at 9.31 a.m.

local time carrying 235 mostly young passengers and a crew of 14. The passengers

were mostly Dutch and young and included three babies and 48 children. Also on

board were four Germans, two Australians, and four Americans.

The

second plane was a Pan Am 747, which had departed Los Angeles the night before

for the Canary Islands with a refueling stop in New York. The flight had been

delayed an hour and a half in L.A. and took five hours to make it to New York.

380 passengers were on board and most of them were retirees eager to board the

Royal Cruise Line's ship Golden Odyssey for a 12-day Mediterranean

cruise.

The

plane wasn't just any 747. It was the Clipper Victor - the first

747. It is the one seen in the news reels taking off in the first commercial

flight of a jumbo jet on January 21, 1970 in New York and landing in London

later that day. This day it was being flown by Captain Victor Grubbs, a 57 year

old with over 21,000 hours of experience as a pilot.

The

KLM's uneventful four-hour trip took them over Belgium, France, and Spain and

would have had them at Los Palmas airport on time but fate intervened. At 12:30

p.m. a terrorist's bomb exploded in the passenger terminal at Los Palmas and a

phoned-in threat to blow up another caused airport officials to close the

airport.

The

KLM flight was diverted along with several other planes to the Canary Islands

other airport - Los Rodeos - where it landed at 1:10 p.m. Captain van Zantent

was asked to park his plane on an unused parallel runway next to a Norwegian

737. Shortly thereafter, a DC-8 and 727 joined them.

Hoping

the Los Palmas airport would soon reopen, Captain van Zantent initially asked

the passengers to stay on board. After about twenty minutes with no sign of the

airport reopening, he relented and the passengers were taken to the terminal. At

that point, one of the passengers, Robina van Lanschot, who was with the company

who had chartered the flight, decided she had seen her passengers through to the

Canaries and decided to call it and day and stay overnight in nearby Santa Cruz.

This decision certainly saved her life.

Captain

van Zantent had more than just inconvenienced passengers to think about. A

number of potentially fatal incidences of crew fatigue in recent years had

stripped KLM pilots of discretion over extending their crews' continuous hours

of service and Captain van Zantent was becoming concerned that he would not be

able to make his return flight without breaking those rules and becoming subject

to prosecution back home. After the passengers departed, he asked for and

received permission to refuel his plane for the trip back home. Unfortunately,

this required bringing out a fuel tanker on the runway - a decision that would

prove fateful.

Around

this time, the Pan Am 747 was approaching Los Palmas nearly 13 hours after

boarding in Los Angeles the previous day. Captain Grubbs, aware of the closure

but also carrying more than enough fuel, had asked air traffic control (ATC) to

allow his plane to remain in a holding pattern pending the reopening of Los

Palmas. Much to his displeasure, ATC denied the request and he was asked to join

the ever-growing line-up of planes on the unused runway of Los Rodeos in

Tenerife.

Captain

Grubbs landed his jumbo at 1:45 or about 35 minutes after the KLM had landed. He

too initially asked his passengers to stay on board though the cabin doors were

opened to allow fresh air in.

Air

traffic control announced that no other bombs had been found at Los Palmas and

that the airport was open again. The KLM was still being refueled but the 737,

DC-8 and a 727 were able to maneuver around it and the Pan Am to make in onto

the runway and to take off. ATC then called the Pan Am and cleared them to line

up for a takeoff. The news was greeted with cheers from the relieved passengers,

which now included two additional Pan Am employees who wanted to take advantage

of the flight to Los Palmas.

But

when it came time for the Pan Am to taxi, it found that it did not appear to

have enough room to get around the KLM and its refueling tanker.

Los

Rodeos had not been designed for large jumbo jets and there was not much space

to get around the KLM 747. Still First Officer Robert Bragg and Flight Engineer

George Warns climbed out of the plane to pace out the amount of space needed to

go around the KLM. Unfortunately, their initial assessment was correct; they

would not be able to leave until after the Dutch jumbo. Meanwhile, the weather

began to deteriorate and fog began to descend on the airport.

By

the time the refueling was complete, it was 4:26 p.m. and fog had reduced

visibility at the airport to as little as 300 meters. Two minutes later the crew

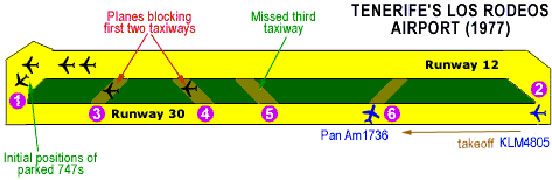

asked for and received permission to backtrack down runway 30 (see diagram

below) where they would exit on the third taxiway (past the other planes) and

onto runway 12 and then turn at the end of runway 12 back onto runway 30 for

takeoff. The communications between the Spanish ATC in the tower and the Dutch

crew were in English and are from the CVR:

ATC: "Taxi to the holding

position for Runway 30. Taxi into the runway. Leave the runway third to your

left."

KLM: "Roger, sir. Entering the

runway at this time. And we go off the runway again for the beginning of Runway

30."

ATC: "Correction. Taxi straight

ahead, uh, for the runway. Make, uh, backtrack."

KLM: "Roger, make a backtrack.

KL4805 is now on the runway."

ATC: "Roger."

KLM (half a minute later): "You

want us to turn left at taxiway one?"

ATC: "Negative, negative. Taxi

straight ahead, uh, up to the end of the runway. Make backtrack."

KLM: "OK, Sir."

At

this point, the fog was so heavy that the ATC could no longer see the planes on

the runway. First officer Bragg of the Pan Am then confirmed that they were to

enter runway 30 while the KLM was still using it:

Pan Am: "Uh, we were instructed to

contact you and also to taxi down the runway. Is that correct?"

ATC: "Affirmative. Taxi into the

runway and, uh, leave the runway third... third to your left."

Pan Am: "Third to the left.

OK."

ATC: "Third one to your left."

According

to the Pan Am's CVR, Captain Grubbs was unclear as to what the Spanish ATC had

said: "I think he said first." Bragg replied: "I'll ask him

again." Unfortunately, both planes were using the same frequency to contact

the ATC and before he could ask he heard the ATC ask the KLM:

ATC: "KL4805, how many taxiway,

uh, did you pass?"

KLM: "I think we just passed

Charlie [taxiway] four now."

ATC: "OK. At the end of the runway make 180 [turn

completely around] and report, uh, ready for ATC clearance."

Meanwhile,

the Pan Am crew were still having difficulty understanding exactly what to do.

First Officer Bragg had a diagram of Los Rodeos Airport which he was referring

to when he said to Captain Grubbs: "This first [taxiway] is a 90 degree

turn." Then he said, "Must be the third... I'll ask him again."

Grubbs then replied "We could probably go in, it's, uh." Bragg then

emphatically says "You've got to make a 90 degree turn!" Bragg then

called ATC:

Pan Am: "Would you confirm that you

want the Clipper 1736 to turn left at the third intersection?"

ATC: "The third one, sir. One, two, three - third

one."

The

Pan Am crew then began going through the pre-takeoff checklist still unsure

exactly where to get off the runway. "That's two!" the captain

exclaimed.

Warns: "Yeah. That's the 45

[degree taxiway] there."

Bragg: "That's this one right

here."

Grubbs: "Yeah, I know "

Warns: "Next one is almost a

45."

Grubbs: "But it does, it goes

ahead. I think it's gonna put us on the taxiway."

Warns: "Maybe he counts these as three."

The

Pan Am plane has just missed the third taxiway and is continuing down the

runway. (This mistake most likely occurred because the third taxiway heads back

at a 135 degree angle toward the parked aircraft (see diagram below) instead of

at the angle of the forth taxiway and because the taxiways were not marked.

Taking the third taxiway, while accident investigators concluded it would have

avoided the accident, would have required two very tight 135 degree turns for a

big aircraft at an airport not designed for big aircraft - the pilots may have

concluded that the ATC couldn't have meant for them to take the third taxiway

when the next taxiway was at an easy 45 degree angle.)

Meanwhile,

the KLM plane has made it to the end of the runway, turned around, completed its

pre-takeoff checklist, and is ready for takeoff. Then Captain van Zantent, who

desperately wants to get his crew in the air, does something unexpected. He

throttles the engine and the plane starts to move forward. First Officer Klaus

Meurs senses this is wrong and says "Wait. We don't have clearance!"

Van Zantent then presses the brakes and asks Meurs to get clearance:

KLM: "KL4805 is now ready for

takeoff. We're waiting for our ATC clearance."

ATC: "KL4805. You are cleared to the Papa beacon.

Climb to and maintain Flight Level 90. Right turn after takeoff. Proceed with

heading 040 until intercepting the 325 radial from Las Palmas VOR."

This

clearance is for after they are airborne and is not takeoff clearance. As

First Officer Meurs began to read back the ATC's message, Van Zantent released

his foot from the brakes and began advancing the throttles for takeoff.

KLM: "Roger, sir, we are cleared to the Papa

beacon, Flight Level 90 until intercepting the 325. We're now at takeoff."

The

ATC clearly believed that this meant the KLM was at takeoff position, awaiting

clearance, at the end of the runway:

ATC: "OK. Standby for takeoff. I

will call you."

Pan Am: "We are still taxiing down the runway!"

Tragically, the KLM only heard the "OK" but never heard the

rest of what the ATC said nor the Pan Am's subsequent message (as confirmed by

the CVR tape) as the Pan Am and ATC were speaking at the same time.

The wheels were literally in motion for this accident to occur and the missed

message was the last chance to avoid it. With Captain Van Zantent and First

Officer Meurs busy 20 seconds into takeoff, only KLM Flight Officer Willem

Schreuder listened to the rest of the exchange:

ATC: "Roger. Pan Am 1736, report

the runway clear."

Pan Am: "OK. Will report when we

are clear."

ATC: "Thank you."

An

alarmed Schreuder then asked "Did he not clear the runway then?"

"Oh yes" was van Zantent's reply as the captain continued his fateful

takeoff. The Pan Am, which had missed the third taxiway and was now approaching

the forth when Captain Grubbs said "Let's get the hell right out of

here." "Yeah ... he's anxious, isn't he?" replied Warns and then

added, "After he's held us up for all this time - now he's in a rush."

1-The planes are parked at the end

of runway 12 with the KLM in front of the Pan Am.

2-The KLM has made it to the end

of runway 30 and is ready for takeoff.

3-The Pan Am has passed the first

taxiway.

4-The Pan Am has passed the second

taxiway.

5-The Pan Am has missed the third

taxiway where it is supposed to exit. The KLM begins to takeoff.

6-The Pan Am tries to get off the

runway but is hit by the KLM.

Just then, Grubbs saw through the fog the unmistakable image of

the lights on the oncoming 747. "There he is! Look at him! Goddamn ... that

son-of-a-bitch is coming!" Bragg cried out "Get off! Get off! Get

off!" as Grubbs desperately pushed the throttles wide open in an attempt to

get the plane off the runway.

Captain Van Zantent finally saw the Pan Am and tried to pull up.

The plane became airborne but not enough to completely miss the Pan Am. It

sheered off the top of the other 747 then remained airborne another 500 feet

before hitting the runway and bursting into flames. All 234 passengers and 14

crew on board the KLM died in the fire.

The

Pan Am burst into flames immediately upon impact. Pan Am First Officer Bragg's

first thought was to reach up and switch off the power to the engines. But he

couldn't. The top of the plane right above his head, where the switch used to

be, was gone.

Many

of those on the side of the aircraft where it had been hit were killed instantly

or quickly by the resulting fire. Those that were fortunate enough to escape the

flames had to risk serious injury by jumping 20 or more feet onto wreckage.

Because

of the fog, the ATC heard the explosions but could not locate where they were

and thus did not know what had happened. When rescue crews finally reached the

scene, they were able to get 70 survivors to the hospitals but nine of them

eventually died due to their injuries. Almost half the crew - including all

those in the cockpit - survived.

Investigation(s)

Although

it happened in Spanish territory, neither the Americans or Dutch would agree to

merely a Spanish investigation. Thus, the Spanish, Dutch, Boeing and the

Americans investigated the disaster - which remains the worst aviation accident

of all-time with a death toll of 583.

More

than 60 investigators were sent to the scene. When KLM officials first heard of

the disaster, they tried to get their best people down to the scene to

investigate. Unaware of the crew list, one of the experts they tried to reach

was Captain van Zantent.

Naturally,

the Dutch blamed the American pilot for not following instructions and getting

off the runway. The Americans blamed the Spanish ATC for not giving clear

instructions and the KLM pilot for taking off without clearance (the Spanish

also cited the KLM pilot's mistake in their report).

Accident

Investigation

There

were many questions regarding the cause of this accident:

1.

Why had Captain van Zanten commenced take off with out the ATC clearance to do

so?

2.

Why had Captain Grubbs been instructed to vacate the runway at taxi way 3, which

would have taken him back towards the main apron, and not T4 which would have

put him on the holding point for runway 30?

3.

Why did the KLM crew not grasp the significance of the Pan Am aircraft's report

that it had not yet cleared the runway, and would report again to the tower when

it did?

Final

conclusion found that Jacob Van Zanten was solely responsible for the accident.

The fundamental factors in the development of the accident were that van Zanten:

1) Took off without being cleared to do so.

2) Did not heed the ATC controller's instruction to stand by for take off.

3) Did not abandon take off when he knew the Pan Am aircraft was still taxiing.

As

with most airplane accidents, several seemingly small events happened which, had

they not, the accident never would have happened. For example, if the bombing

more than 100 miles away at another airport had not happened or if the phony

threat of another bombing had not been made, those planes never would have been

at Los Rodeos. If the Pan Am wouldn't have been 1 1/2 hours late out of Los

Angeles, it would have been to Los Palmas before the closure. If the Pan Am had

been allowed to remain in a holding pattern, it would not have been at

Los Rodeos. If the KLM hadn't taken the time to refuel, or if the weather hadn't

deteriorated, the visibility would have been higher when it took off. If the Pan

Am had been able to make it around the KLM when it was refueling, it wouldn't

have been there when the KLM was taking off. If the Pan Am hadn't missed the

third taxiway, it would have avoided a collision. If the Pan Am and ATC hadn't

been speaking at the same time, the KLM would have heard the instruction to wait

for clearance. If the visibility had been even slightly better, both aircraft

may have had enough time to avoid one another. Even still, the KLM almost missed

the Pan Am on the runway.

Report dated

October 1978 released by Civil Aviation Department, Spain, in English

History of the flight

The KLM Boeing 747, registration PH-BUF, took off

from Schiphol Airport (Amsterdam) at 0900 hours on 27 March 1977, en route to

Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. This flight was part of the Charter Series KL

4805/4806 Amsterdam-Las Palmas (Canary Islands)-Amsterdam operated by KLM on

behalf of the Holland International Travel Group (H.I.N.T.), Rijswijk-Z.H.

The Boeing 747 registration N736PA, flight number

1736, left Los Angeles International Airport, California, United States, on 26

March 1977, local date, at 0129Z hours, arriving at John F. Kennedy

International Airport at 0617Z hours. After the aeroplane was refueled and a

crew change effected, it took off for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain) at

0742Z.

While the aeroplanes were en route to Las Palmas, a

bomb exploded in the airport passenger terminal. On account of this incident and

of a warning regarding a possible second bomb, the airport was closed.

Therefore, KLM 4805 was diverted to Los Rodeos (Tenerife) Airport, arriving at

1338Z on 27 March 1977. For the same reason, PAA 1736 proceeded to the same

airport, which was its alternate, landing at 1415.

At first the KLM passengers were not allowed to

leave the aeroplane, but after about twenty minutes they were all transported to

the terminal building by bus. On alighting from the bus, they received cards

identifying them as passengers in transit on Flight KL 4805. Later, all the

passengers bearded KLM 4805 expect the H.I.N.T. Company guide, who remained in

Tenerife.

When Las Palmas Airport was opened to traffic once

more, the PAA 1736 crew prepared to proceed to Las Palmas, which was the

flight's planned destination.

When they attempted to taxi on the taxiway leading

to runway 12, where they had been parked with four other aeroplanes on account

of the congestion caused by the number of flights diverted to Tenerife, they

discovered that it was blocked by KLM Boeing 747, Flight 4805, which was located

between PAA 1736 and the entrance to the active runway. The first officer and

the flight engineer left the aeroplane and measured the clearance left by the

KLM aircraft, reaching the conclusion that it was insufficient to allow PAA 1736

to pass by, obliging them to writ until the former had started to taxi.

The passengers of PAA 1736 did not leave the

aeroplane during the whole time that it remained in the airport.

KLM 4805 called the tower at 1656 requesting

permission to taxi. It was authorized to do so and at 1658 requested to

backtrack on runway 12 for take-off on runway 30. The tower controller first

cleared the KLM flight to taxi in the holding Position for runway 30 by taxiing

down the main runway and leaving it by the (third) taxiway to its left. KLM 4805

acknowledged receipt of this message from the tower, stating that it was at that

moment taxiing on the runway, which it would leave by the first taxiway in order

to proceed to the approach end of runway 30. The tower controller immediately

issued an amended clearance, instructing it to continue to taxi to the end of

the runway, where it should proceed to backtrack. The KLM flight confirmed that

it had received the message, that it would backtrack, and that it was taxiing

down the main runway. The tower signalled its approval, whereupon KLM 4805

immediately asked the tower again if what they had asked it to do was to turn

left on taxiway one. The tower replied in the negative and repeated that it

should continue on to the end of the runway and there backtrack.

Finally, at 1659, KLM 4805 replied, "O.K.,

sir." At 1702, the PAA aeroplane called the tower to request confirmation

that it should taxi down the runway. The tower controller confirmed this, also

adding that they should leave the runway by the third taxiway to their left. At

1703:00, in reply to the tower controller's query to KLM 4805 as to how many

runway exits they had passed, the latter confirmed that at that moment they were

passing by taxiway C-4. The tower controller told KLM 4805, "O.K., at the

end of the runway make one eighty and report ready for ATC clearance."

In response to a query from KLM 4805, the tower

controller advised both aeroplanes KLM 4805 and PAA 1736 that the runway centre

line lights were out of service. The controller also reiterated to PAA 1736 that

they were to leave the main runway via the third taxiway to their left and that

they should report leaving the runway. At the times indicated, the following

conversations took place between the tower and the KLM 4805 and PAA 1736

aeroplanes.

Times taken from KLM CVR.

|

1705:44.6 |

KLM |

The KLM ... four eight

zero five is now ready for take-off ... uh and we're waiting for our ATC

clearance. |

|

1705:53.41 |

Tower |

KLM eight seven zero

five you are cleared to the Papa Beacon climb to and maintain flight level

nine zero right turn after take-off proceed with heading zero four zero

until intercepting the three two five radial from Las Palmas VOR.

(1706:08.09) |

|

1706:09.61

|

KLM |

Ah roger, sir, we're

cleared to the Papa Beacon flight level nine zero, right turn out zero

four zero until intercepting the three two five and we're now (at

take-off). (1706:17.9) |

|

1706:18.19 |

Tower |

Stand by for take-off,

I will call you. |

|

1706:19.39

|

|

A squeal is heard

(1706:22.06) |

|

1706:21.92

|

PanAm |

Clipper one seven

three six. |

|

1706:25.47

|

Tower |

Ah Papa Alpha one

seven three six report when runway clear (1706:28.89) |

|

1706:29.59

|

PanAm |

OK, will report when

we're clear. (1706:30.69) |

|

1706:31.69

|

Tower |

Thank you |

Subsequently, KLM 4805, which had released its

brakes to start take-off. run 20 seconds before this communication took place,

collided with the PAA aeroplane.

The control tower received no further communications

from PAA 1736, nor from KLM 4805.

There were no eyewitnesses to the collision. Place

of accident The accident took place on the runway of Tenerife Airport (Los

Rodeos) at latitude 28° 28' 30" N and longitude 16° 19' 50" W. The

field elevation is 2 073 ft (632 m).

Date The accident occurred on 27 March 1977, at 17

hours 06 minutes 50 seconds GMT.

Aids to

navigation

KLM 4805

The aircraft was equipped with the following aids to

navigation:

|

VOR/ILS: |

|

|

|

Bendix RNA-26C |

108-117, 95 MHz |

3 systems |

|

|

|

|

|

Marker Beacon: |

|

|

|

Bendix MKA-28C |

75 MHz |

1 system |

|

|

|

|

|

ADF : |

|

|

|

Collins 51Y-7 |

190-1750 kHz |

2 systems |

|

|

|

|

|

DME: |

|

|

|

Collins 860 e-3 |

1000 MHz |

2 systems |

|

|

|

|

|

ATC Radar Beacon: |

|

|

|

Collins 621A-3 |

1030-1090 MHz |

2 Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

Weather Radar: |

|

|

|

Bendix RDR-1F |

9375 MHz |

2 systems |

|

|

|

|

|

Radio Altimeter: |

|

|

|

Collins 860F-1 |

4300 MHz |

3 systems |

|

|

|

|

|

Inertial Navigation System: |

|

|

|

Delco Carousel IV |

|

3 systems |

|

|

|

|

|

Emergency Radio Beacon: |

|

|

|

Garret Rescue-99 |

121.5/243 MHz |

4 systems |

PAA 1736

The aircraft was equipped with the following aids to navigation:

|

Description |

Make |

Model |

No. of systems |

|

ADF |

Collins |

51Y4 |

2 systems |

|

DME |

Collins |

621A-3 |

2 systems |

|

VOR/ILS |

Collins |

51RV2B |

2 systems |

|

Radar |

(AVQ-30X) RCA |

MI-592041 |

2 systems |

|

Radio Altimeter |

Bendix |

ALA-51A |

2 systems |

|

Radar Beacon |

Collins |

621A-3 |

2 systems |

|

Inertial Navigation System |

Delco Elect |

7883450-041 |

3 systems |

KLM 4805

The aircraft was equipped with the following communication instruments:

|

HF COM: |

|

|

|

Collins 61 8T-2 |

2-30 MHz |

2 systems |

|

VHF COM: |

|

|

|

Collins 618M-2B |

118-135.97 MHz |

3 systems |

|

Selcall |

|

|

|

Motorola |

NA-135 1 Dual Decoder |

|

|

Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR): |

|

|

|

Sundstrand AV-557B |

|

1 system |

PAA 1736

The aircraft was equipped with the following communication instruments:

|

Description |

Make |

Model |

No. of systems |

|

VHF |

King |

KTR-9100A |

2 systems |

|

HF |

Collins |

61182 |

2systems |

|

Audio-Interphone |

Ford |

1-X00-185-3 |

1 system |

|

Selcal |

Motorola |

NA-126AV |

1 system |

Aerodrome and ground facilities

Los Rodeos (Tenerife) Airport is located at an

elevation of 632 m (2 073 ft). The 12/30 runway is 3 400 m (11 155 ft) long, and

has two stopways of 60 m. It is 45 m wide. The elevation at the approach end of

runway 30 is 2 001 ft and that of runway 12 is 2 064 ft. The highest point of

the airport is near the intersection of taxiway 3.

Because of its altitude and location in a sort of

hollow between mountains, the airport has distinctive weather conditions, with

frequent presence of low-lying clouds.

The Los Rodeos Airport was equipped with the following radio aids to navigation at the time of the accident:

|

VOR/DME, TFN 112.5 Mc |

Normal operation |

|

ILS 110.3 Mc |

Normal operation |

|

FP Beacon, 243 kc |

Normal operation

|

|

NDB, TX, 410 kc |

Normal operation |

|

NDB, LD, 370 kc |

Out of service (NOTAM II 573/76) |

Los Rodeos Airport was equipped with the following

visual approach aids at the time of the accident:

|

Approach lights |

In service |

|

VASIS |

In service(that of runway 12 was being tested) |

|

Flashers on runway 30 |

In service |

|

Precision approach lighting |

In service |

|

Runway centre line indicated |

In service |

The airport was equipped with the following beacon

marking system at the time of the accident:

|

Lighting of the flight runway |

in service |

|

Lighting of the taxiway |

in service |

The runway centre line lights were out of service

(NOTAM II 92/77).

The air-ground communication radio frequencies in

service at the time of the accident were as follows:

- 119.7 Mc for Approach

- 118.7 Mc for Taxiing

The following NOTAMs were in force at the time of

the accident, with regard to the Los Rodeos Airport radio aids and air-ground

visual and communication aids:

- On 15.3.1977, NOTAM

I, National no. 643, International No. 382, contained the following text:

"Runway 12/30 centre line lights out of order until further

notice." (This NOTAM was changed to NOTAM II-A, no. 92/77 on

15.3.1977.)

- On 19.3.1977, NOTAM I,· National no. 791, International no. 463, contained the following text: "Frequencies 121.7 and 118.7 MHz being tested." (On 25.311977, this NOTAM was changed to NOTAM II-A, no. 108/77).

Magneto phone recording points in the Tenerife

control tower equipment

Radio

Radio channels recording

The radio channels recording is performed by

operator posts in the following manner.

The reception signals heard over the loudspeaker are

recorded immediately after the loudspeaker line amplifier at the point indicated

in the "Rx loudspeaker record" diagram.

The reception signals heard by earphones are

recorded immediately after the earphone line amplifier at the point indicated in

the "Rx earphone" diagram.

The transmission signals are recorded immediately

before the transmission line amplifier at the point indicated in the "Tx

record" diagram.

All these signals are appropriately mixed in order

to be fed into the magneto phone recording channels in the following manner:

General radio recording

All the signals received by the Tower receivers,

whether coming from aircraft or from the airport's own ground transmitters, are

recorded at a point immediately before the radio control system, indicated in

the "Rx lines record" diagram.

These signals coming from all the receivers are

conveniently mixed and fed into Channel 12 of the magneto phone.

Telephony

Telephone transmissions and messages received are

also recorded by operator posts and taken from the points indicated on the

diagram as "telephone record" and "L.C. loudspeaker record",

being conveniently mixed and fed into the magneto phone the following manner:

Flight

recorders

KLM 4805

KLM Boeing 747, registration PH-BUF, flight number

4805, was equipped with a digital flight data recorder (DFDR) and a cockpit

voice recorder (CVR).

Digital flight data recorder (DFDR)

This was a Sundstrand model 573 A with 41

parameters. The box was considerably damaged by the impact and fire. The front

aluminum panel was missing, so that the tape covering could be seen. Therefore,

no serial number was immediately available, and this was obtained from the KLM

records.

PAA 1736

Boeing 747, registration N736PA, belonging to Pan

American World Airways Company, flight number 1736, was equipped with a digital

flight data recorder (DFDR) by Lockheed Aircraft Service Co. (LAS), Model 209-E,

serial number 375. The DFDR was not damaged by fire and suffered only sight

damage due to the impact.

It was also equipped with a cockpit voice recorder

(CVR), model Fairchild A-100, serial number 504.

Both recorders were transported, duly sealed, by the

Spanish Civil Aviation Authorities to the N.T.S.B. in Washington for

transcription.

Tests and

investigations

In the investigation of this accident, the following

tapes play a very important role: the two digital flight recorders (DFDR), one

belonging to the Pan American Boeing 747, N736PA, and the other to the KLM

Boeing 747, PH-BUF; the two cockpit voice recorders (CVR), one of which also

belonged to each aeroplane ; and the Tenerife Control Tower transmission tapes.

The KLM DFDR and CVR were located in the aeroplane ’s tail section. The Pan Am

DFDR was located in the tail section and the CVR in the cockpit.

KLM DFDR

The KLM DFDR box was considerably damaged by the

impact and fire. The front aluminum panel was missing, so that the tape cover

was visible. Therefore, no serial numbers were immediately available, and these

had to be obtained from the KLM Company records. The unit's stainless steel

cover was deformed and it could not be taken out of the structure. It had to be

removed by opening the welded joint by means of a hammer and chisel. At first

large scissors were used to try and .cut the casing in order to open it, but

this attempt failed. Once the casing had been removed, the shock-proof cover was

separated from the electronic section by means of an iron lever (the cover was

attached to the electronic section with an anti-shock mounting). The lid bolts

were removed from the shock-proof cover, and it was taken off. The DFDR heat

insulation material had been singed and separated from the lid.

The teflon sheaths of the magnetic recording wire

connectors were not burned and had kept their original colors. These would

probably have been discolored by temperatures above their MST temperatures of

4000 to 4780F. The nylon cord used to tie the wire reels was discolored. The MST

for the nylon used is 2500 to 3000F. There was no proof of melted welding, which

indicates that the temperature did not reach 3600F. Therefore, it is probable

that the temperature to which the cover was subjected was between 2500 and

3600F.

Burn marks were found on the steel disc covering the

upper reel, as well as on the reading head and on the reels themselves. The

aluminum reels had a slightly golden color. This shade of color could have been

caused by some material which gave off gases inside the cover during the fire.

The tape was found intact, without breakages. It was

smudged and discolored in the places where it was revolving around the reels and

the heads at the moment that the recorder stopped working.

The mechanism had a burned area at its point of

contact with the tape. It was possible to remove the heaviest bits from the tape

by using alcohol, cotton and cotton tips. It was possible to read all the data

on the tape after adequate cleaning.

The whole of the tape except for the last six meters

was on the bottom reel. The accident data were on track 1.

DFDR tapes are made of a material called Vicalloy.

They are 0.64 cm wide and 247 m long. Four tracks are recorded - two forward and

two backward. Only one track records at a time and each track lasts

approximately 6.25 hours, making a total time of 25 hours. There are two

recording heads - one going forward and the other backward - as well as two

playback and two eraser heads. The tape recording speed is 1.09 cm/sec and the

playback speed is 14.2 cm/sec.

The Pan American FDR

The PAA aircraft FDR was not damaged by fire, and

only slightly damaged by the impact. The inner and outer seals (dated 22 March

1977) were intact, as were the four screw seals for the box (S/N 1413).

The FDR box is a shock-proof casing. The heat

indicator is outside the tape cover. A temperature indicator (TEM PLATE) outside

the tape cover showed a temperature of between 1100 and 1200F, indicating that

this was the highest temperature to which the box had been exposed.

When the tape covering was opened up, the tape was

found to be intact, without any breakages and in excellent condition. On account

of the strong impact to which this unit was subjected, the tape had come off the

reel and two revolutions had fallen off the lower reel. The tape was handled

carefully and replaced on the reels. Most of it was on the lover reel, with

approximately 28 m remaining on the upper reel.

There was no problem with playback; The data were

found between 105-113 m on track 3.

The FDR LAS tape is based on Mylar, with an

instrumentation grade 1.0 mm thick, 0.64 cm wide and approximately 145 m long

(of which about 142 m are used for recording). Six tracks are registered, three

forward and three backward. Only one track is recorded at a time and each one

lasts approximately 4.2 hours, making a total recording time of 25 hours. There

are two recording heads (one going forward and the other backward) and two

playback heads. There are no eraser heads. The tape's recording speed is 0.94

cm/sec and the playback speed is 30 cm/sec.

Boeing 747, N736PA, cockpit voice recorder

As previously stated, the Pan American aeroplane's

CVR was an A-100, with its identification plate missing. Pan American records

show that the serial number was 504. This Fairchild CVR was only blackened. The

tape was removed, copied and transcribed in accordance with normal procedures.

This CVR has four channels, which are recorded

simultaneously. Recording is continuous, but only the last 30 minutes are kept.

On one of the channels, that corresponding to the cockpit microphone area, all

the latter's sounds are recorded. On the other three channels are recorded the

communications from the Captain, First Officer and Flight Engineer,

respectively.

Transcription of this flight recorder was carried

out in the N.T.S.B. laboratories in Washington.

KLM Company Boeing 747,'registration PH-BUF,

cockpit voice recorder

It was not possible to transcribe this aeroplane's

CVR at the N.T.S.B. because there was no reading equipment for this recorder in

the N.T.S.B. laboratories, as the U.S. airline companies had not acquired this

type of CVR. It was taken by a representative of the Spanish Civil Aviation

Authorities to the Sundstrand equipment manufacturers in Seattle (U.S.A.) on 5

April 1977. Members of the N.T.S.B. and KLM accompanied this representative.

When copies of the CVR were taken to the N.T.S.B., it was observed that there

were noises and echoes, and for this reason the said representative returned to

Sundstrand on April 7. New copies were made, partially suppressing the noises

and echoes and obtaining recordings of satisfactory quality.

Like the Pan Am CVR, this CVR has four channels,

which are:

| Channel 1: Flight engineer's communications. | |

| Channel 2: Co-pilot's communications | |

| Channel 3: Captain's communications | |

| Channel 4: Sounds in cockpit area. |

The transcription of the said tapes on paper was

carried out in the N.T.S.B. laboratories.

Tape of Tenerife Control Tower's

communications

The Spanish authorities made a cassette copy of the

Tenerife Control Tower tape available. The original is in the, hands and under

the custody of said Authorities. A problem arose when an attempt was made to

correlate the times of the tower tape with those of the Pan Am and KLM CVRs. The

codified signal and the conversation in the tower were recorded simultaneously

on the cassette and it was difficult t, read the time signal. Moreover, the tape

apparently changed speeds, making it difficult to correlate the time elapsed.

Therefore, the Pan Am CVR was used as a basic time reference, being in perfect

agreement with this aircraft's FDR.

The GMT time was determined by means of a

transcription of the tower tape, whose chronology it was possible to ascertain

with an acceptable degree of accuracy. This technique proved to be satisfactory

as it was in agreement with the Pan Am and KLM CVR times. The PAA and KLM speeds

were adjusted in such a way that the aeroplanes' 400 Hz energy was synchronized

with the audio laboratory clock and, therefore, with the real time. The Pan Am

CVR times were the most accurate during the initial period, on account of the

Sundstrand B 557 B recording method. The degree of error is negligible. The

Sundstrand tape is not continuous, but rather reverses its direction every 15

minutes.

The tape's basic time reference was determined by

simultaneously recording the CVR and a digital watch on a video tape.

Subsequently the Spanish Authorities made copies of

the control tower tape available; these did not give rise to time correlation

problems.

Limits on duty time of Dutch crews

Until a few years ago, the Flight Captain was

able, at his own discretion, to extend the limit on his crew's activity in order

to complete the service. However, this was recently changed in the sense of

imposing absolute rigidity with regard to the limit of activity. The captain is

forbidden to exceed it and, in case he should do so, may be prosecuted under the

law.

Moreover, until December 1976, it was very

easy to fix the said limit of activity by taking only a few factors into

account, but this calculation has now been made enormously complicated and in

practice it is not possible to determine it in the cockpit. For this reason it

is strongly recommended that the Company be contacted in order to determine it.

This was the situation in Tenerife, and for

this reason the captain spoke by HF to his company's operations office in

Amsterdam. There they told him that if he was able to take off before a certain

time it would seem that there would be no problems, but that if there was any

risk of exceeding the limit they would send a telex to Las Palmas.

This uncertainty of the crew, who were not

able to determine their time limit exactly, must have constituted an important

psychological factor.

Those who serviced

the KLM aeroplane in Tenerife stated that the crew appeared calm and friendly.

Nevertheless, they perhaps felt a certain subconscious - though exteriorly

repressed - irritation caused by the fact that the service was turning out so

badly, with the possible suspension of the Las Palmas-Amsterdam flight and the

resulting alteration of each person's plans, which would be aggravated by the

existence of other possible sources of lateness such as ATC delays, traffic

congestion in Las Palmas, etc.

Care. This can be divided into voluntary and involuntary, or subconscious. The

increase in one brings with it a decrease in the other.

Visibility both before and during the accident was

very variable. It changed from 1 500 to 300 m or less in very short periods of

time. This undoubtedly caused an increase in subconscious care to the detriment

of conscious care, part of which was already directed toward take-off

preparation (completing of check-lists, taxiing with reduced visibility,

decision to take off or to leave the runway clear and execute a difficult 180

degree turn with a 747 on a 45 m runway, in fog).

Fixation. Two kinds: a fixation on what is

seen, with a consequently diminished capacity to assimilate what is heard, and

another fixation on trying to overcome the threat posed by a further reduction

of the already precarious visibility. Fated with this threat, the way to meet it

was either by taking off as soon as possible, or by testing the visibility once

again and possibly refraining from taking off (a possibility which certainly

must have been considered by the KLM captain).

Relaxation. After having executed the

difficult 180 degree turn, which must have coincided with a momentary

improvement in the visibility (as proved by the CVR, because shortly before

arriving at the runway approach they turned off the wind- screen wipers), the

crew must have felt a sudden feeling of relief which increased their desire to

finally overcome the ground problems: the desire to be airborne.

Possible biometrical factors

Fatigue. Although within reasonable

limits, fatigue began to be felt.

Overload. Problems were accumulating for the captain to a degree far greater than

that of a normal flight. Likewise for the co-pilot, who did not have much

experience in 747s.

Low-frequency electromagnetic waves. According to certain studies, these have a deleterious effect on man's

intellectual performance (e.g., 400-cycle alternative current waves in an

aircraft).

Noise and vibration. Their level is quite high in a 747

cockpit.

Other possible causes

Route and pilot-instruction experience. Although the captain had flown

for many years on European and intercontinental routes, he had been an

instructor for more than ten years, which relatively diminished his familiarity

with route flying. Moreover, on simulated flights, which are customary in flight

instruction, the training pilot normally assumes the role of controller - that

is, he issues take-off clearances. In many cases no communications whatsoever

are used in simulated flights, and for this reason take-off takes place without

clearance.

Authority in the cockpit. Although nothing abnormal can be

deduced from the CVR, the fact exists that a co-pilot not very experienced with

747s was flying with one of the pilots of greatest prestige in the company who

was, moreover, KLM's chief flying instructor and who had certified him fit to be

a crew member for this type of aeroplane . in case of doubt. these circumstances

could have induced the co-pilot not to ask any questions and to assume that this

captain was always right.

Crash report source : NTSB